june 14, 2019 - Tornabuoni Art

Mapping the world with Alighiero Boetti

Tornabuoni Art presents a first-of-its-kind survey of the Mappe in a special project at Art Basel 2019

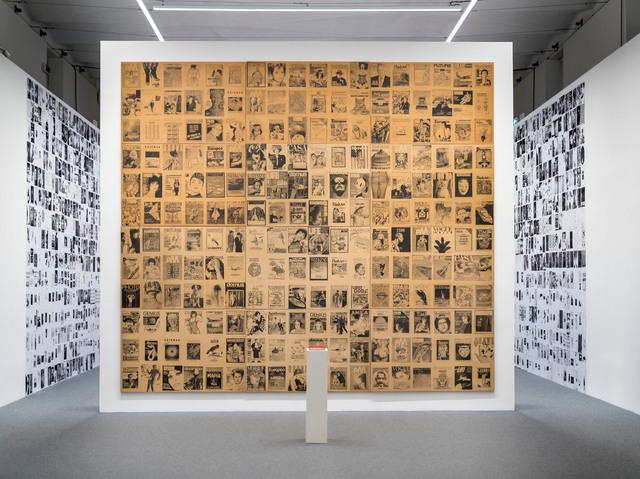

Until now, only Tate Modern (2011) and MoMA (2012) – in their joint #alighieroboetti retrospective – have brought together examples of every type of Mappa Boetti ever made under one roof. In an unprecedented event for any gallery at an art fair, Tornabuoni Art brings the whole range together at Art Basel. Each Mappa is unique but can nonetheless be traced back to eight different types, various examples of which will be shown on Tornabuoni’s stand.

With this project, Tornabuoni Art continues its tradition of presenting museum-quality solo booths at Art Basel that explore a particular series or aspect of an artist’s production – from Paolo Scheggi’s landmark 1966 Venice Biennale presentation in 2015, to Salvatore Scarpitta’s racing cars in 2016, Lucio Fontana’s Fine di Dio series in 2017 and Alberto Burri’s Plastiche in 2018.

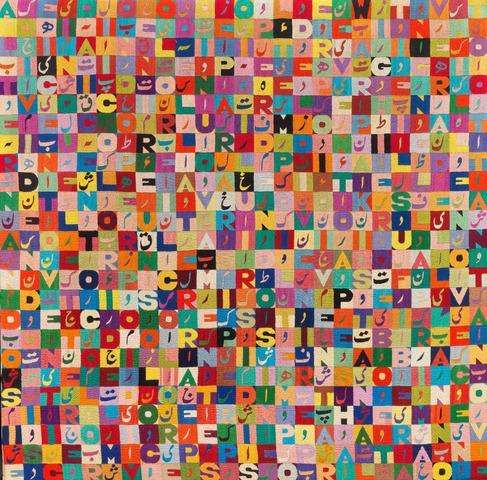

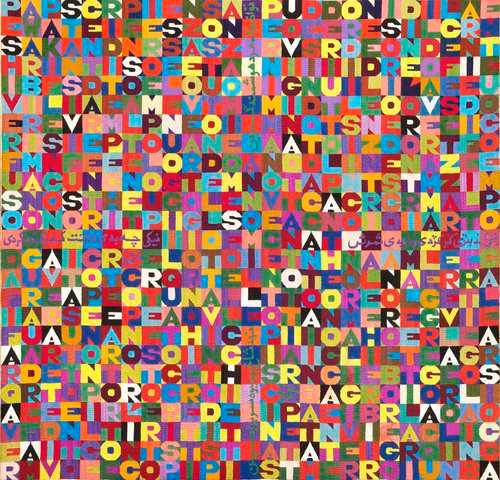

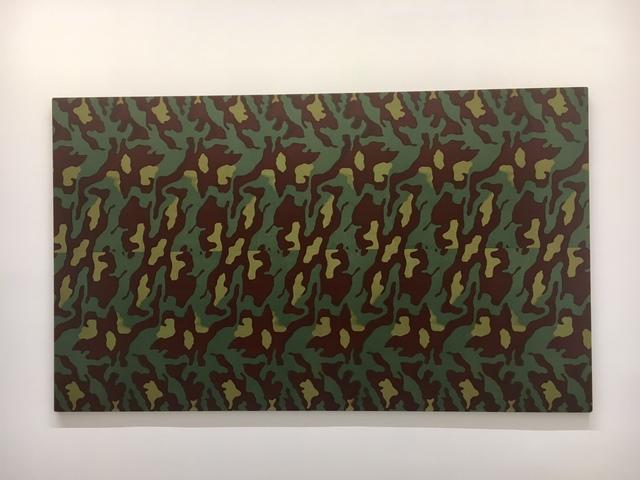

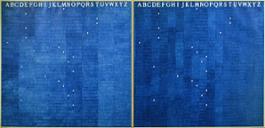

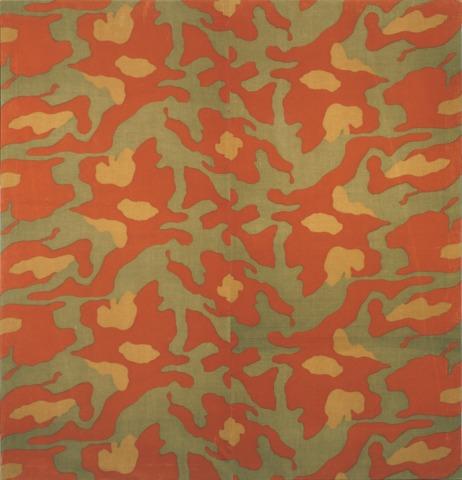

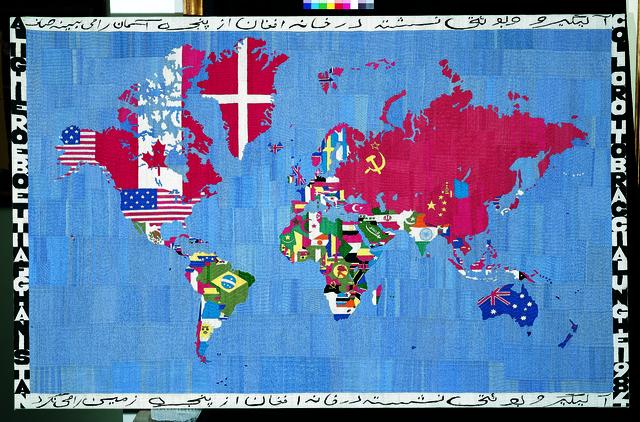

Alighiero Boetti (1940-1994) made his famous Mappe (maps) throughout his career. Together they form a monumental “work in progress” – numbering around 200 works – charting more than 20 years of global historical and geopolitical change. Tornabuoni Art’s stand at Art Basel this year will bring together, for the first time, all eight different types of Mappe that Boetti created, from his first, in 1968, to the last, made in 1994, the year of his death.

This stand represents Tornabuoni Art’s return to Boetti, following the groundbreaking show ‘Alighiero Boetti: Minimum/Maximum’ at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, organized in collaboration with the Boetti Archive, on the occasion of the Venice Biennale 2017.

Mapping a changing World

The Mappe constitute an evolving chronicle of the changes in global geopolitics between the 1970s and the 1990s. In addition, they combine Boetti’s conceptual vision with the handicraft of anonymous Afghan women embroiderers. Boetti had a profound love for Afghanistan, which he visited regularly between 1971 and 1979, before the Soviet invasion, and he suffered the country’s wars and its losses as if they were his own. After the Soviet invasion, he even managed to track down the country’s refugees in neighbouring Pakistan to employ them to continue producing embroideries for him.

Boetti believed that his role as an artist was, above all, to be a “creator of rules”. In the case of the Mappe, the rule is that every nation must be represented by the colours and shapes of its national flag at the time of each map’s creation. Because of this rule, we can identify the year, or period, of each map thanks to the geopolitical make-up of the nations represented.

Conceptually speaking, the Mappe are works of art that date themselves – just like a calendar, they represent a particular moment in time. For example, works from 1971 record important moments in the global de-colonisation process, with the inclusion of Tanzania, newly independent since 1964; works made from 1978-79 include

the newly independent states of Zaire, Angola, Mozambique and Sudan. Boetti’s own strong dislike of Muammar Gaddafi means that Libya’s all-green flag didn’t appear until 1979. In the face of Apartheid in South Africa, Namibia’s flag is shown until 1973, but is then left as a blank white space until it achieved independence in 1991. From 1979, Boetti records the rise to power of Khomeini in Iran. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, he gave the local embroiderers the choice of representing their country with its old three-colour flag, a white space, or the word “Khalq” (“people”) on a monochrome background. After the fall of the USSR, Boetti started using the new Russian flag on his final monumental maps of 1992-94.

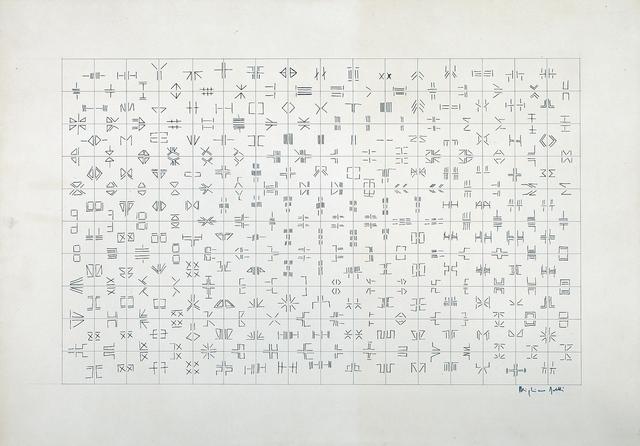

The first Mappe

Boetti first bought a map of the world from the newsstand in the late 1960s, which he coloured in according to each country’s national flag – the Planisfero Politico, of 1969, is on display at the stand. During his first trip to Kabul in 1971, Boetti noticed the ubiquity of embroidery – it was possible to have clothes, carpets, embroidered in all manner of ways with relative ease. The democratic nature of this craft, which was practiced exclusively by women throughout the country and in vast numbers, struck a chord with the artist, who designed and commissioned the first Mappa there and then. This work is on view at Art Basel. It was the women who embroidered, but since men couldn’t be in the same space, he would send female friends – and later his daughter Agata – to check on progress.

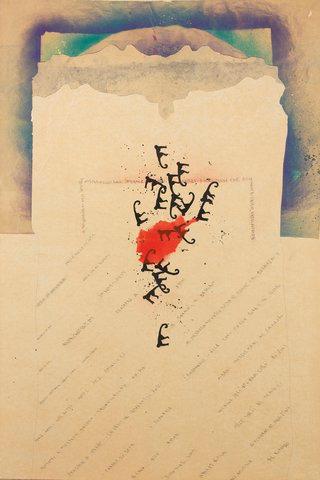

Later Boetti designed the Mappe in Italy and then sent the cloth to Afghanistan to be embroidered. Once completed, the works would be sent back to Rome. Often on these voyages, the works themselves would be subjected to all kinds of political events and mishaps. When the Afghans fled to Pakistan during the Soviet invasion, some of these works served as blankets and bags, thus becoming almost unreadable through wear and tear. Boetti managed to salvage other works, deliberately leaving visible signs of these vicissitudes because they conformed to his belief that “things are born out of necessity and chance”.

Maggiori informazioni nel comunicato stampa da scaricare

Share

Share Share via mail

Share via mail  Automotive

Automotive Sport

Sport Events

Events Art&Culture

Art&Culture Design

Design Fashion&Beauty

Fashion&Beauty Food&Hospitality

Food&Hospitality Technology

Technology Nautica

Nautica Racing

Racing Excellence

Excellence Corporate

Corporate OffBeat

OffBeat Green

Green Gift

Gift Pop

Pop Heritage

Heritage Entertainment

Entertainment Health & Wellness

Health & Wellness