september 11, 2015 - Comune di Milano

The Great Mother: the iconography of motherhood in art and visual culture of the Twentieth century

The Great Mother, curated by Massimiliano Gioni, promoted by Comune di #milano | Cultura, conceived and produced by Fondazione Nicola Trussardi together with Palazzo Reale for ExpoinCittà 2015, realised with the support of BNL – BNP Paribas Group, open to the public from August 26th to November 15th 2015 in the main floor of Palazzo Reale.

The exhibition—a pivotal #event in the Autumn programme of ExpoinCittà—is a collaboration between the public and private sectors aimed at bringing the most innovative forms of #contemporaryart into Milan’s most prestigious and pivotal exhibition venue, Palazzo Reale.

With over 400 works by 139 international artists, writers and directors alongside documents and other descriptive artifacts – on loan from some twenty museums around the world, as well as foundations, archives, private collections and galleries — and an exhibition layout that covers 2000 square meters (20,000 square feet), stretching through 20 rooms on the main floor of Palazzo Reale, The Great Mother analyzes the iconography of motherhood in art and visual culture of the Twentieth century, from early avant-garde movements to the present.

From the Venuses of the Stone Age to the bad girls of the postfeminist era, and through centuries of religious works depicting innumerable maternity scenes, the histories of art and culture has often centered on the figure of the mother, often adopted as a symbol of creativity and metaphor for art itself. In the more familiar version of “Mamma”, it is also a stereotype closely tied to the image of Italy. The Great Mother is an exhibition about women’s power: not just the life-giving creative power of mothers, but above all, the power denied to women and the power won by women over the course of the twentieth century. From the representation of motherhood, the exhibition The Great Mother moves out to trace a history of women's empowerment, chronicling gender struggles, sexual politics, and clashes between tradition and emancipation.

Conceived as a temporary museum that blends art history with visual culture, the exhibition reconstructs a story that spans the twentieth century, exploring female icons and clichés of femininity, and developing a complex reflection on woman as an active participant in representation, no longer just a passive subject of it.

The show opens with a presentation of the archive of Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn, who throughout her life, starting in the Thirties, gathered thousands of images of female idols, mothers, matrons, Venuses and prehistoric deities into a vast iconographic collection that was used by Carl Gustav Jung, Erich Neumann and many other psychologists and anthropologists researching the archetype of the great mother and the matriarchal cultures of prehistory.

A few decades earlier, the writings of Sigmund Freud and his observations about the Oedipus complex had transformed family ties and the mother-child relationship into a drama of sexual desire and repressed tension that would leave its mark on the entire twentieth century. These themes recur, transfigured, in the drawings and etchings of Alfred Kubin and Edvard Munch from the same period. In the first rooms of the exhibition, these delirious visions are alternated with the didactic image of motherhood popularized in the late nineteenth century by the photographs of Gertrude Käsebier and the motion pictures of the first female filmmaker, Alice Guy-Blaché.

A major section of the exhibition focuses on women in the early avant-garde movements, specifically, in Futurism, Dada, and Surrealism. Showing the work of women artists alongside the male artists who have dominated the histories of these movements, it highlights both contradictory and complementary attitudes that defined modernity while analyzing the radical transformations of gender roles that accompanied the profound economic and societal changes of the early twentieth century. A study of the position of women within Futurism— with works by Benedetta, Umberto Boccioni, Giannina Censi, Valentine De Saint-Point, Mina Loy, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Marisa Mori, Regina, Rosa Rosà and others— reveals the clash between impulses for reform and forces of repression in Italy at the time. The rooms dedicated to Dada center on the emerging myth of the automated, mechanical woman—"the daughter born without a mother”, as Francis Picabia would call her—and her place within the rapidly changing social landscape of the 1910s and 1920s, in both Europe and America. From the bachelor machines of Marcel Duchamp, Picabia, and Man Ray, to the puppets and dolls of Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Emmy Hennings and Hannah Höch, to the irreverent performances of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, the show describes the dangerous liaisons woven between biology, mechanics and desire in the early twentieth century.

Surrealism’s fascination with women is analyzed through an extraordinary presentation of fifty original collages from Max Ernst’s The Hundred Headless Woman, shown alongside the works and documents of André Breton, Hans Bellmer, Salvador Dalí, and others. Exploring the aesthetic and ethical implications of the Surrealist obsession with femininity, the exhibition foregrounds the works of women artists who both embraced and rejected the rhetoric of the movement, in which they found tools for liberation but also oppressive sexual stereotypes. This section includes masterpieces and famous works by Leonora Carrington, Frida Kahlo, Dora Maar, Lee Miller, Meret Oppenheim, Dorothea Tanning, Remedios Varo, Unica Zürn, and other artists of the time whose fame was long overshadowed by their male colleagues.

These works are intertwined with a selection of scenes of motherhood from silent films and documents about Fascist birth-rate policies, alongside images of sorrowing mothers and proud heroines in Neorealist cinema. In this choral family album, the image of the mother often overlaps with the idea of nation, creating troubling associations between body and state.

The conceptual epicenter of the second part of the exhibition is a selection of works by Louise Bourgeois, who assimilated and transformed the influence of Surrealism, melding it with references to archaic cultures, to create a personal mythology of extraordinary symbolic power.

Many women artists who emerged in the Sixties and Seventies—including Magdalena Abakanowicz, Ida Applebroog, Lynda Benglis, Judy Chicago, Eva Hesse, Dorothy Iannone, Yayoi Kusama, Anna Maria Maiolino, Ana Mendieta, Marisa Merz, Annette Messager and others—created a new vocabulary of forms, full of biological references, through which these artists declared the centrality of the female body, often associating it with the powers of nature and the earth.

In more or less the same period—parallel to the feminist movements that will be presented in the exhibition through a range of documents—very different artists such as Carla Accardi, Joan Jonas, Mary Kelly, Yoko Ono, Martha Rosler, VALIE EXPORT and others portrayed the domestic sphere as a place of tension and oppression, calling into question the division of labor and gender roles in the home and family.

Hierarchies and power dynamics are also challenged in the works of Sherrie Levine, Lee Lozano, and Elaine Sturtevant who— in different ways—fight against the traditional modes of production and reproduction. Using copies and replicas or completely refusing to create anything new, these artists imagine new models of property and new forms of ownership that sidestep patriarchal authority.

By juxtaposing found images and collage, Barbara Kruger, Ketty La Rocca, Suzanne Santoro, and others began waging a semiotic guerrilla war that criticized the slogans and messages of the media, deconstructing the image of woman and mother created by mass communication.

The works of artists as different as Katharina Fritsch, Cindy Sherman, and Rosemarie Trockel—active since the Eighties—reclaim art history, blending genres and iconographic references to the theme of maternity and religious painting and sculpture.

The Nineties saw the rise of various artists whose work is characterized by an aggressive simplicity. In a now-legendary series, Rineke Dijkstra portrays mothers and their children a few hours after birth. Sarah Lucas composes sculptures and assemblages out of androgynous forms; Catherine Opie documents the lives and desires of gay and S/M communities in Los Angeles; and painters as different as Marlene Dumas and Nicole Eisenman portray motherhood as a joy and burden, liberation and imprisonment.

Pipilotti Rist mixes Baroque painting with music video esthetics in a new work that transforms the ceiling of a room in Palazzo Reale into an electronic fresco, while Rachel Harrison records the apparitions of the Virgin Mary in an American suburb.

The works of Nathalie Djurberg, Robert Gober, Keith Edmier, Kiki Smith, Gillian Wearing and others outline a post-human perspective in which technology and biology open up new horizons for overcoming old gender roles.

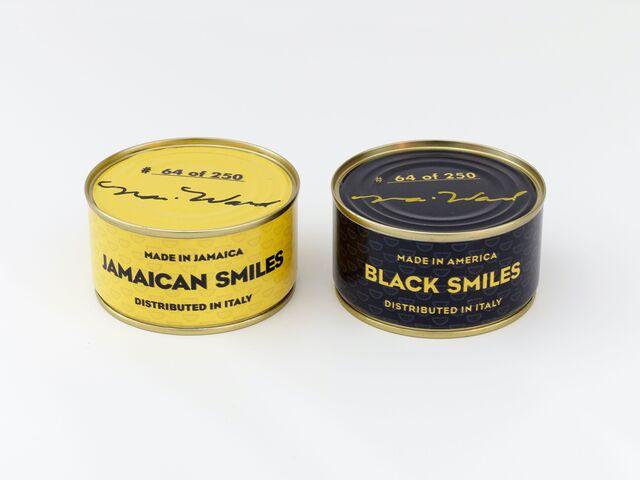

The exhibition is rounded out by many important installations by Jeff Koons, Thomas Schütte, Nari Ward and significant works by Thomas Bayrle, Constantin Brancusi, Maurizio Cattelan, Lucio Fontana, Kara Walker, to cite just a few.

In her famous video Grosse Fatigue, which won a Silver Lion at the last Venice Biennale, Camille Henrot analyzes creation myths and the genesis of the universe, narrating the birth of Mother Earth.

An extraordinary series of photographs by Lennart Nilsson – the first photographer to capture the image of a living fetus with an endoscope—offers a hyperrealistic vision of maternity, transforming it into a spectacle bordering on science fiction.

The most recent works also include the first presentation in Italy of the famous Brown Sisters series by Nicholas Nixon, who has taken a group portrait of the siblings every year for the last forty years.

Together, these works and many others on view delineate an image of the mother as a projection of individual and collective desires, anxieties and aspirations, both male and female. Perhaps a less reassuring vision than the one we are used to from advertising and other rhetoric, but unquestionably more complex and powerful.

Comune di #milano | Cultura and Fondazione Nicola Trussardi present

The Great Mother

curated by Massimiliano Gioni

An exhibition promoted by the Cultural Office of the City of Milan Conceived and produced by Fondazione Nicola Trussardi

in partnership with Palazzo Reale

for ExpoinCittà 2015

Palazzo Reale, Milan

August 26 – November 15, 2015

Italian

Italian  Share

Share Share via mail

Share via mail  Automotive

Automotive Sport

Sport Events

Events Art&Culture

Art&Culture Design

Design Fashion&Beauty

Fashion&Beauty Food&Hospitality

Food&Hospitality Technology

Technology Nautica

Nautica Racing

Racing Excellence

Excellence Corporate

Corporate OffBeat

OffBeat Green

Green Gift

Gift Pop

Pop Heritage

Heritage Entertainment

Entertainment Health & Wellness

Health & Wellness